Not just for the butterflies : the multiple boons of being a Butterflyway Ranger

The deeply personal, social and political joys of volunteering through the Butterflyway Project

It’s my third year, this year, of being a Ranger for the David Suzuki Foundation’s Butterflyway project. Started as the Canadian chapter for the Homegrown National Park (now a separate initiative), this is a Canadian charity’s phenomenal answer to the growing insect biodiversity crisis that’s threatening our way of life.

Native plants really are where it’s at in terms of insect conservation, yet they can do so much more than just provide a source of food for all the wildlife we know so well! In fact, you can do something about it by becoming a Ranger yourself. If you’re wanting to get in on the action, applications have opened yesterday, and close on Feb. 19.

Act one — Help the bees… but how?

One thing really led to another after last pandemic. I’ve been a native plant seed-head (pardon the pun) since.

I was stranded inside when I realized it was Spring 2021, and that the bees needed our help. When I heard of the No Mow May movement as started in the U.K., I thought it was a logical step : let’s grow flowers for the bees!

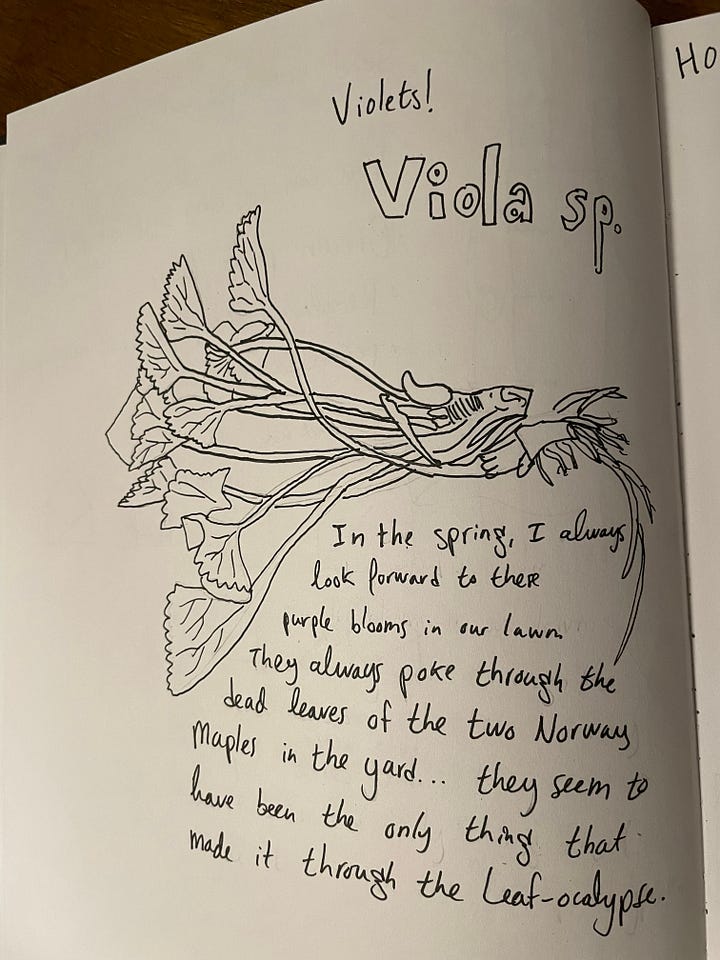

I did the right thing at first — I downloaded iNaturalist for the first time and honed in on all the species I could get my eyes on. I saw lots of miner bees in the neighbourhood, that thrived on bare patches of ground. I also saw violets (Viola sororia), which I read was an important native host plant for the Fritillary butterfly. It was the start of a journey.

So I started giving out printed signs, without much thought, to my neighbours.

All throughout April and May of that year, I did local campaigns for watershed organizations, I spoke on the radio, made the front page of the local paper, and many people responded with a resounding… lack of mowing!

I did not know what a native plant was then. I used the comfrey — Symphytum sp. — as an example (as seen on the sign — a non-native plant hard to eradicate), because as a gardener, it was what I knew attracted the bumblebees.

Until a friend presented me to his friend, who knew a lot about native plants — then thanks to my new friend, I landed a student job at Pollinator Partnership Canada and got to work on an animated video. I gotta say, I was hooked.

With my animation & motion design courses under the belt, and all this knowledge around me, I did the logical thing to do. Here’s the result of that summer, thanks to an amazing team of colleagues.

After a year-long freelance stint in motion design; a few jobs in local environmental organizations; lots of Doug Tallamy reads; an online symposium about seeds; 2023 came knocking.

By that time, I was back at it : native plants were my calling. I felt like the time was ripe to apply to the Butterflyway Project.

Act two — Nature inquiry and joining the Butterflyway

We just talked how I quickly realized that “helping the bees” was a bit more elbow grease than doing “nothing”; not mowing can only get you so far. Time to step it up a little!

Luckily, the Butterflyway project exists for the purpose of building pollinator gardens. 1,800 Rangers have been trained so far to do this:

More than 116,500 native wildflowers and grasses planted

Approximately 3,150 trees and shrubs planted

7,400 habitat gardens established

139 Butterflyways established (a Butterflyway [means creating] 12 or more habitat gardens in close proximity)

Indeed, building a Butterflyway can be quite the endeavour. This was the goal I agreed on while signing up : all of 12 gardens? After three years, I definitely haven’t used up all my Butterflyway Project signs, and I ought to!

At the same time, I discovered Wild Wonder Foundation and nature journaling.

These two things really opened the respective cans of worms, namely, of activism and introspection. That’s what I mean by deeply personal : nature’s like that for me.

Then, there’s the social. 1,800 Butterflyway Rangers? That’s a lot of new friends!

We have our fair share of friends in New Brunswick; we’ve been having tea and cookies with some local Rangers for a while, and it’s always fun. We chat over discussing what the next addition to the pollinator garden’s gonna be, and sometimes talk about plants and politics.

Speaking of things political, tides were changing in my local community. The No Mow May buzz made waves, so much so that two years later the old 20-centimeter bylaws on lawn growth were starting to be obsolete. That’s when my hometown — Dieppe — became one of the first municipalities to make way for flowers and eliminate unenforceable language that is so commonplace in municipal bylaws.

It’s impossible to know how much of an impact I had on that decision, but now living right in the neighboring town, I feel like I played a part.

Act three — A trip to Ontario

I’ll be honest — after I started working at Nature NB in late 2023, things blurred a bit for me in terms of the 12 habitat gardens I set out to plant as a volunteer ranger. Nature NB is the organization that distributes Swamp Milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), the native host plant for the Monarch Butterfly, across the province. That way, I feel like my work contributes to many more gardens than I can ever fathom.

That’s how I feel like activism in the Butterflyway goes way beyond just planting flowers by yourself — it makes way for meaningful change.

After discovering about the Ottawa Wildflower Seed Library, I set out to do my own Seed Library in Moncton to get the most native plants out in people’s yards. Then came this new project called Sharing our Nature, that you’re reading right now.

Thanks to the funding I received from Nature Canada, I met so many new friends out in Ontario thanks to this work, I can’t even recall how many three-hour conversations I had on plants!

That’s my story with the Butterflyway project — one not only of hope, but of a very supportive community. I feel like everywhere I go, I can find people I hold common ground with.

I’ll end on that note: many adventures await for those who put in the hours, and I find it’s all worth it at the end!